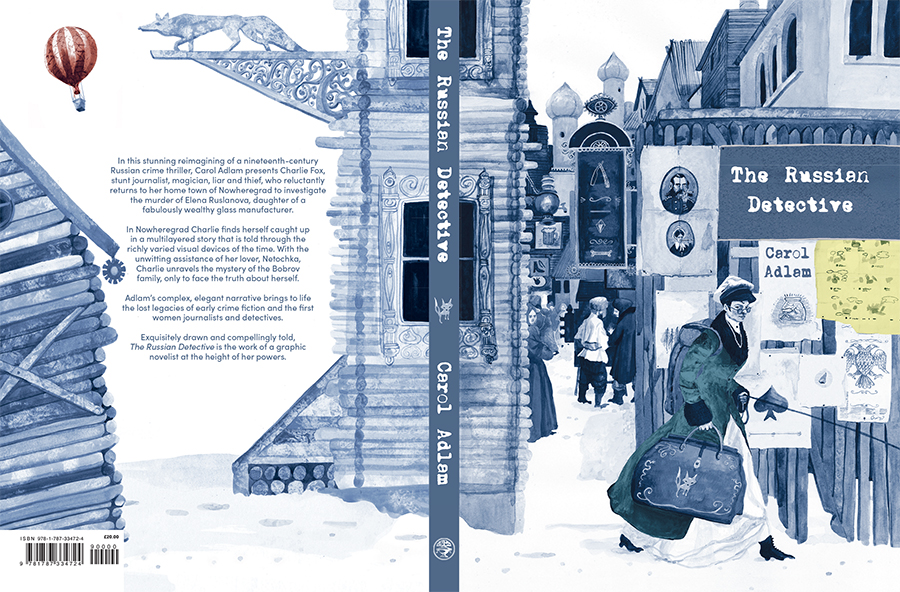

The Russian Detective is a 120-pp. graphic novel created by author-illustrator Carol Adlam and published by the internationally acclaimed Jonathan Cape graphic novel list / Viking (Penguin Random House) in 2024. In it Adlam presents a new character: Charlotta Ivanovna, aka Charlie Fox, magician, liar, trickster, thief, and a ‘stunt journalist’, who travels to the provincial town of Nowheregrad where she investigates the murder of Elena Ruslanova, daughter of a wealthy glass magnate.

Key source text: Semyon Panov

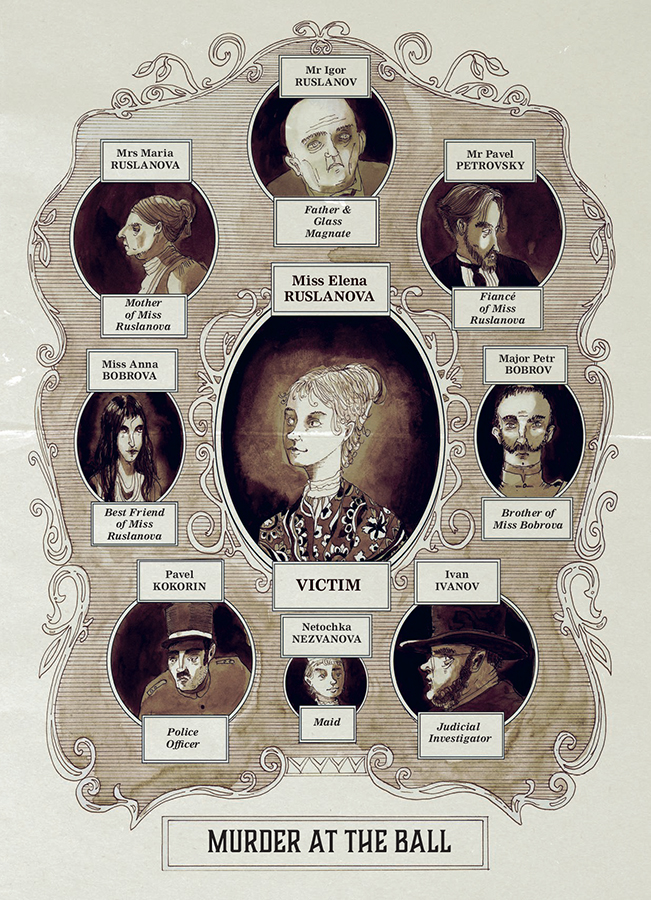

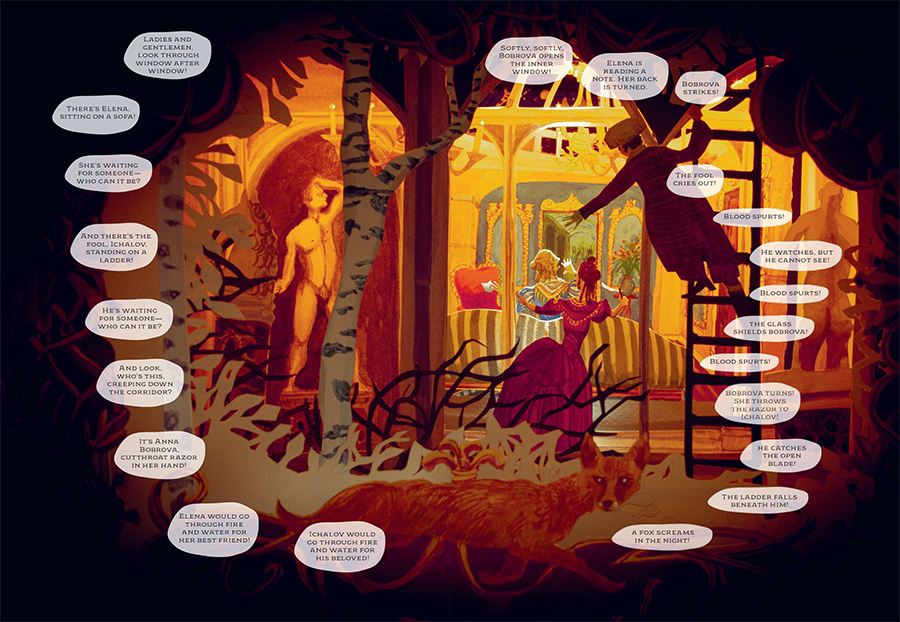

The key source text of The Russian Detective is Semyon Panov’s novella Tri suda, ili ubiistvo vo vremia bala (Three Courts, or Murder At the Ball, 1876). The main characters in The Russian Detective (with the exception of Charlotta Ivanovna and Netochka Nezvanovna) are drawn from Panov’s work: these include Elena Ruslanova (the murder victim), Anna Bobvrova (her best friend), the Judicial Investigator, and Police Officer Kokorin.

In The Russian Detective Adlam frames the original text in a story of her own making, which is a response to the ‘lost’ genre of early Russian crime fiction as a whole. Nevertheless her work references many features from Panov’s text and the wider body of crime fiction, e.g. showcasing the figure of the Judicial Investigator and the role of the police and of early forensic science, as well as exploring the porous relationship between undercover journalism and criminal investigation.

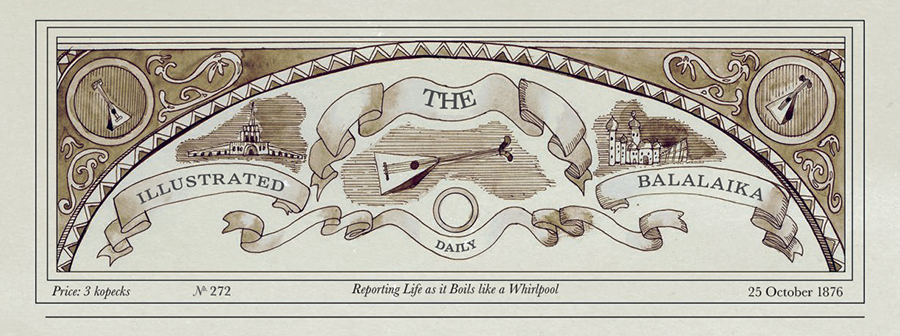

The Russian Detective is deliberately intertextual, situating the world of ‘pulp’ or popular crime fiction in the wider context of Russian literature that is now considered ‘canonical’, and deliberately unsettling the relationship between the two. For instance, the main character is a journalist for a fictional St Petersburg newspaper called The Daily Balalaika: this is modelled on the real-life tabloid the Sankt-Peterburgskii Listok (the St Petersburg Leaf), which – like many other newspapers of the time (e.g. Suvorin’s Novoe Vremia) – employed women as undercover investigators because of their ability to pass unnoticed.

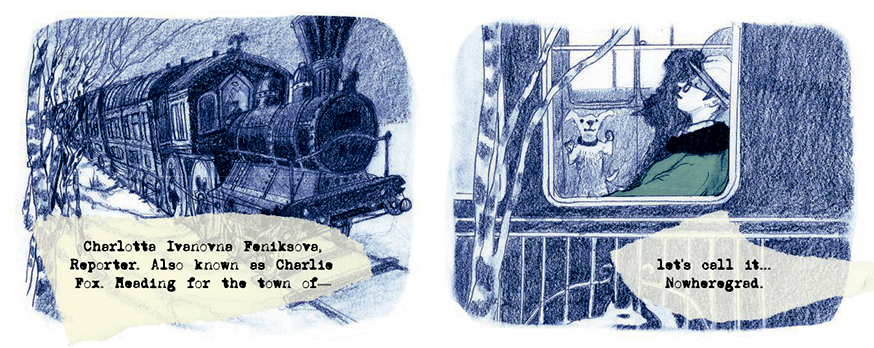

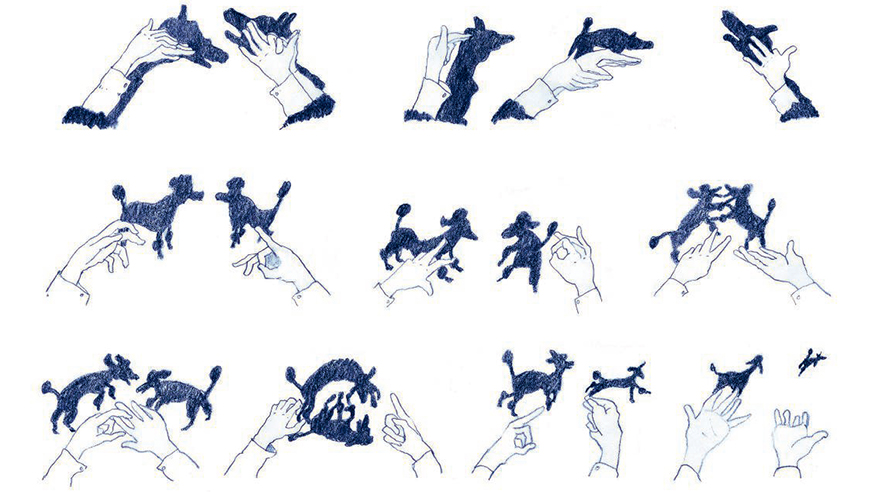

Charlotta is sent to a fictional provincial town, Nowheregrad (which references the town of ‘N’ in Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls). On the train she encounters Fedor Dostoevsky, and contrives to have him arrested for a theft she herself commits. While in Nowheregrad Charlotta discovers that her job on the newspaper has been taken by Semyon Panov, who appears here as a court reporter and son of the chief of police. Adlam also inserts passing references to other works of Russian literature: her lover Netochka Nezvanovna (‘Nameless Nobody’) is the name of the heroine of Dosteovsky’s work of the same name; we hear passing references to Mrs Karenina, Mrs Marmeladova and others; the shadow puppets Charlotta throws on the wall of the train are the runaway poodles that feature in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman; she herself is inspired by the mysterious governess of the same name in Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard (a deliberate anachronism).

Adlam also shows us the rich visual world of the 1870s, which was an eclectic and rapidly changing mixture of new and old technologies and different visual languages, aimed at a variety of audiences, for purposes ranging from documentary reporting to spectacle and entertainment. To this end the story is iterated through many visual languages, including old Sunday supplement comics, lubki (Russian woodblock prints) –

as well as lithographic engravings, ‘family tree’ bookplates, type book, thaumatrope, zoetrope effects, shadow puppets, a Pepper’s ghost illusion, a Magic Lantern show, stamps and censor’s marks, a Claude mirror, a magic mirror (cylindrical anamorphosis), and a peepshow. Readers are invited to consider visual technologies of the late C19th, and in the context of piecing together a crime mystery, to consider the functions and relative truth expectations of the many viewing codes contained within.

The Russian Detective challenges reader expectations about the genre of crime fiction and broadens understanding of global culture by introducing readers to overlooked, non-canonical Eastern European visual and literary traditions. It is designed to make a major intervention in the ambitions and direction of anglophone graphic literature, which is largely oriented towards biography and the contemporary world, and in which historical crime fiction rarely features.

Process

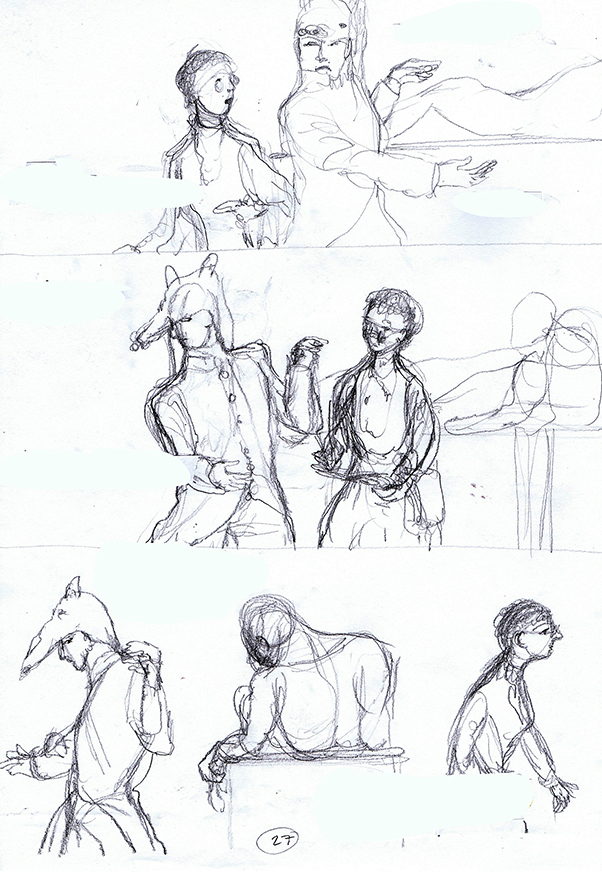

The Russian Detective took Adlam four years to research, write, and draw, from 2019-2023. The process began with the selectIon of a base script with Claire Whitehead. Panov’s text was chosen for its spectacular and unusual setting in a 50-room mansion, the layout of which is so complex that the Judicial Investigator has to call for an architect to map the location when the crime is discovered, and which features a locked room with a glass ceiling. Adlam’s process begins with a script, which went through three iterations; this was then used to produce detailed full-size pencil roughs which included the layout of text as well as elaboration of linework and tonal information. These are then used to create the artwork (examples below).

The above examples show how pencil roughs are indicative only, allowing further decisions to be made about placement, proportion and content. The context of Example 1 is that the Judicial Investigator has asked everyone to stand in the exact position they were when the victim’s scream was heard; here, Major Bobrov stands in a ‘frozen’ dance pose (a clue is that his dance partner is missing), while he and Charlotta exchange words. The statue between them was changed from a man to a wild boar in order to repeat the ‘animal’ theme that runs throughout the book (also indicated by Bobrov wearing a wolf’s head at the fancy-dress ball, and Charlotta’s own nom de plume of ‘the Fox’). Example 2 shows Charlotta’s dream, which features a bear, a cockerel, guards, and a weeping maid (Netochka Nezvanovna): here, there are no significant changes between rough work and the final image, apart from the removal of a guard in the background and the placement of the maid. In Example 3, Charlotta leaves Nowheregrad after a dramatic showdown with Major Bobrov. In the rough work she is shown looking back while Major Bobrov and his mother press against the window, hands raised, and Netochka offers her her hat and bag. The rough work offered an opportunity to rethink this scene substantially, increasing its tension both thematically and visually. In the final piece Major Bobrov has his back to the window, and is saying the words ‘Put the gun down, mother!’; meanwhile, Charlotta has escaped and is dragging a reluctant Netochka with her; the Judicial Investigator and Kokorin examine the body of the dead woman’s fiancé, Petrovsky; and Charlotta’s little dog, Igoryok, is caught mid-leap as he jumps down from the pedestal where he has been waiting for Charlotta. Such interplay between roughs (often over many iterations) and final artwork of changes is a critical part of the creative process.

All the artwork in The Russian Detective was made by hand, with digital colour added in some cases. Materials and techniques used include graphite, coloured pencil, ink, charcoal, gouache, watercolour, photography, 3-d build, Photoshop to add colour and tweak. A Pepper’s Ghost was projected with an ipad and shown at presentations. The Magic Mirror is a custom-cut piece of stainless-steel, polished stair rail. The peepshow was made from cardboard with cotton string, bicycle lights, a ribbon, black cloth, and luminous paint, and then photographed to form the centre spread (above); this has also been shown at presentations.

Reception

The Russian Detective was a Guardian Best Book / Best Graphic Novel pick for 2024; Observer / Guardian Book of the Month in May 2024, and Page 45 Graphic Novel of the Month in May 2024. Other press includes a review in Times Literary Supplement in June 2024 and author interview in the slow journalism quarterly Delayed Gratification.